Building a Soldier’s Story Using War Diaries

My father came from a military family. Both of his grandfathers and at least one of his great-grandfathers were in the British Army in the Victorian era. My grandfather and other relatives served in the First World War. Two great-uncles were in the British Army between the wars.

My father’s family moved to Canada from England in 1928, and my father, his father and his two brothers joined the British Columbia (Duke of Connaught’s Own) Regiment, also known as The Dukes, as militia in the mid-1930s. All the boys had been musicians from when they were children, so they joined the regimental band.

When my father finished school in the spring of 1939, several months before the onset of World War II, he enlisted in the navy. The moment war was declared, my grandfather moved into full-time service, but was discharged shortly after for health reasons resulting from being gassed in WWI. My father’s brother Vincent signed up for regular service in The Dukes as soon as he was of legal age to do so. Younger brother Harry tried to follow his brothers to war, but was too young and was turned down.

I wanted to know as much as possible about my ancestor’s military service.

As part of my family research, I wanted to know as much as possible about my ancestor’s military service. I was lucky in that I inherited my father’s belongings, which included his original navy service record and a variety of memorabilia from his time in the navy.

But I also wanted to find out about my uncle’s service. My father told us that Vincent had been in Europe during the push from Normandy to Germany after D-Day. Uncle Vince, however, never talked about the war in our presence. In fact, we were told that he hardly ever discussed his war-time service with anyone. This was in contrast to my father, who talked about his experiences all the time.

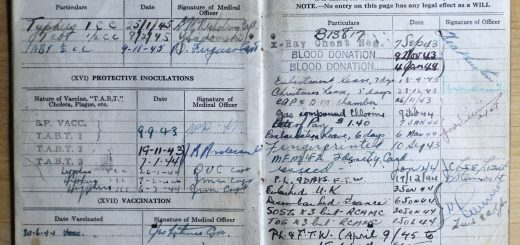

So, I ordered Vincent’s service records from Library and Archives Canada, and many months later they arrived in the post.

I savoured every piece of paper in the envelope…

I savoured every piece of paper in the envelope, which had details of qualifications, leaves and relocations, and also his marriage to an English girl in April 1944 — and the birth of their daughter 11 months later.

As I read through the documentation, I was reminded of a story my mother had told us when we were young. In 1940, Vincent’s regiment was leaving for an undisclosed destination, and my mother had taken his mother to see the soldiers off. Someone in the family kept the newspaper from that day, and we were shown the article about The Dukes departure, which contained the famous photograph, “Wait for me, Daddy.”

Somewhere in that line of soldiers is Private Vincent Lowe (“Wait for me Daddy” taken by photographer Claude P. Dettloff, published 1 October 1940 in The Daily Province Newspaper)

The information in Vincent’s service record was interesting but provided no details after he left England. In fact, the document showed the date he embarked for France — 22 July 1944 (six weeks after D-Day) — and then nothing until he returned to England in June of 1945. I wondered how I could fill in that year and consulted with fellow genealogists I knew had military expertise. I was advised to turn to the “war diaries.” Unfamiliar with these records, I learned that war diaries are the official journals or logs that record the day-to-day activities of a military division, brigade, battalion, squadron, company, or platoon.

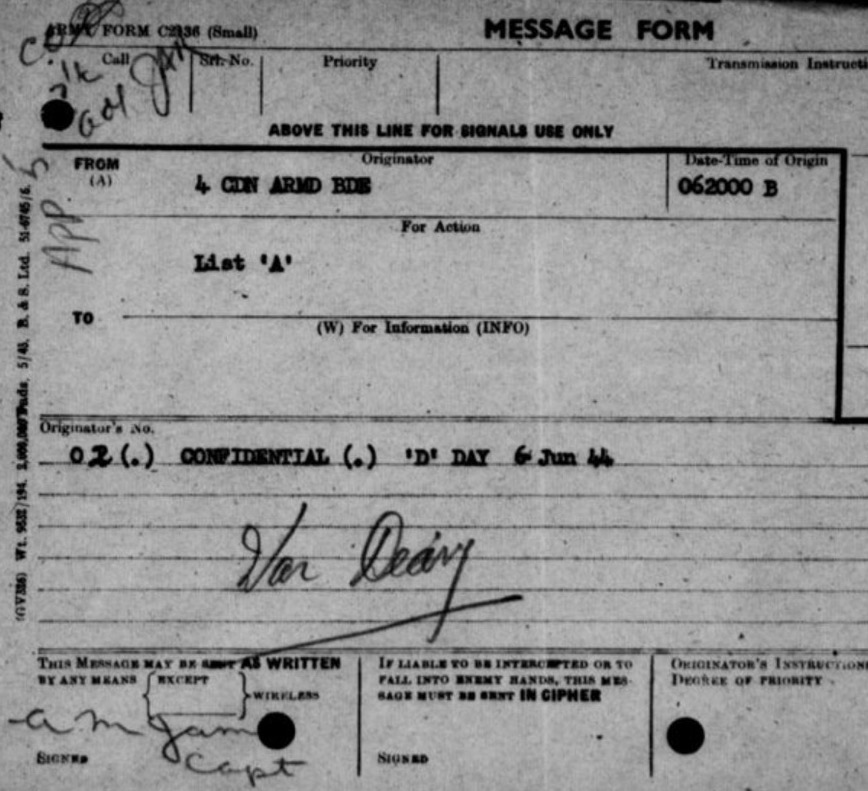

An online search found that the war diaries I needed, those for Canadian regiments for World War II, had been scanned and were available at a website called Heritage Canadiana. However, the scans had not been indexed, and the file names offered no clue as to the regiment, date or any other important information a researcher might need (the file names may be microfilm reel numbers). Researching might mean browsing hundreds or thousands of images until I found the ones related to my uncle’s regiment.

Initially discouraged, I kept digging hoping to unearth a version that showed what each of the films covered. I discovered that a member of the Canada at War online forum had created an index showing the regiment name, and, in some cases, dates with direct links to the images. (That forum is now gone, but the index has been published on WARTIMES.ca.)

My research showed that the British Columbia (Duke of Connaught’s) Regiment had become the 28 Canadian Armoured Regiment. I found that name in the index and when I clicked on the link was taken to the correct scanned images at Heritage Canadiana.

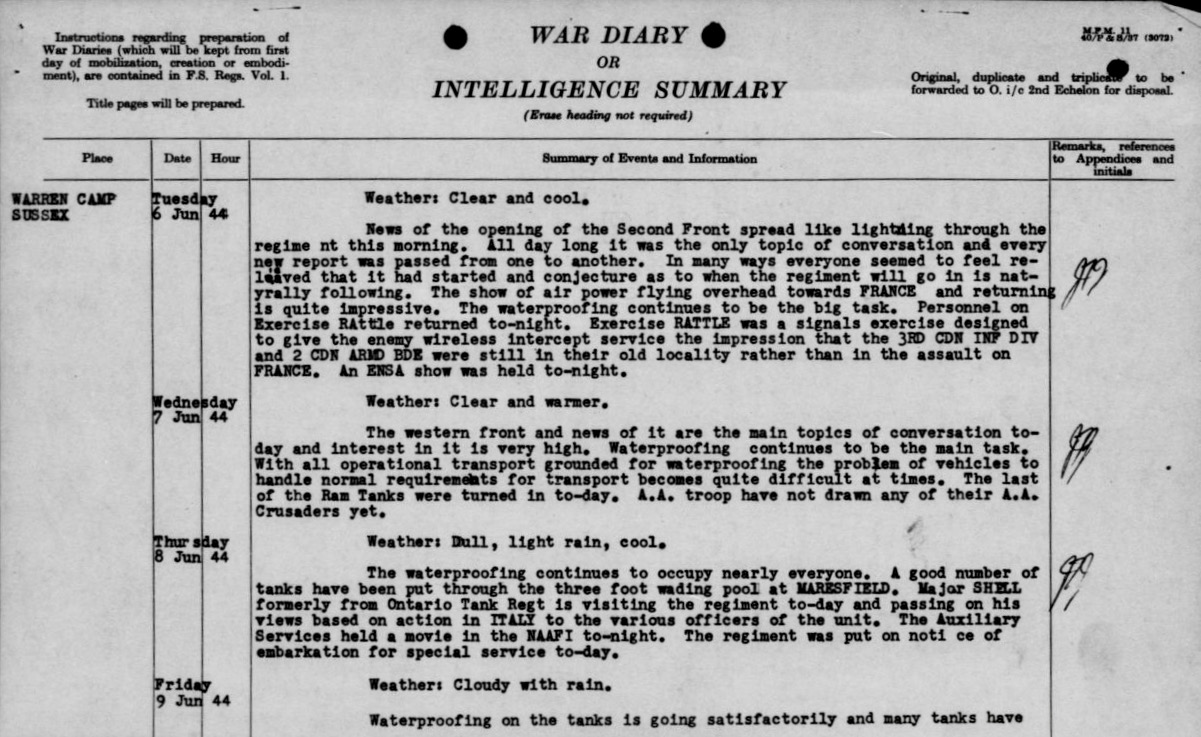

The daily accounts of the regiment for the first couple of years of the war were brief and basic, often consisting of weather reports and training notes.

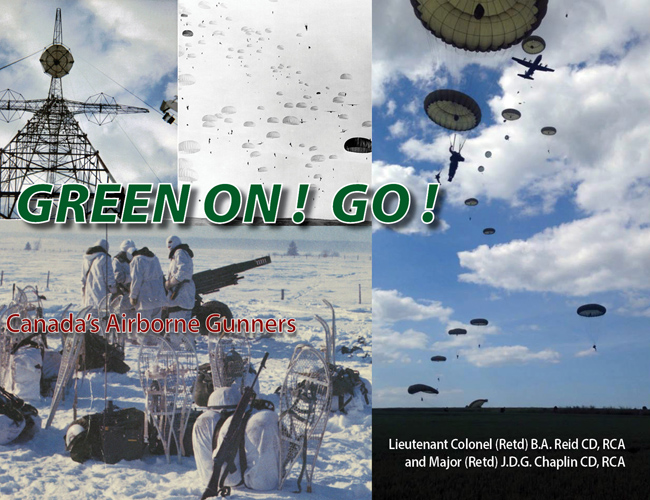

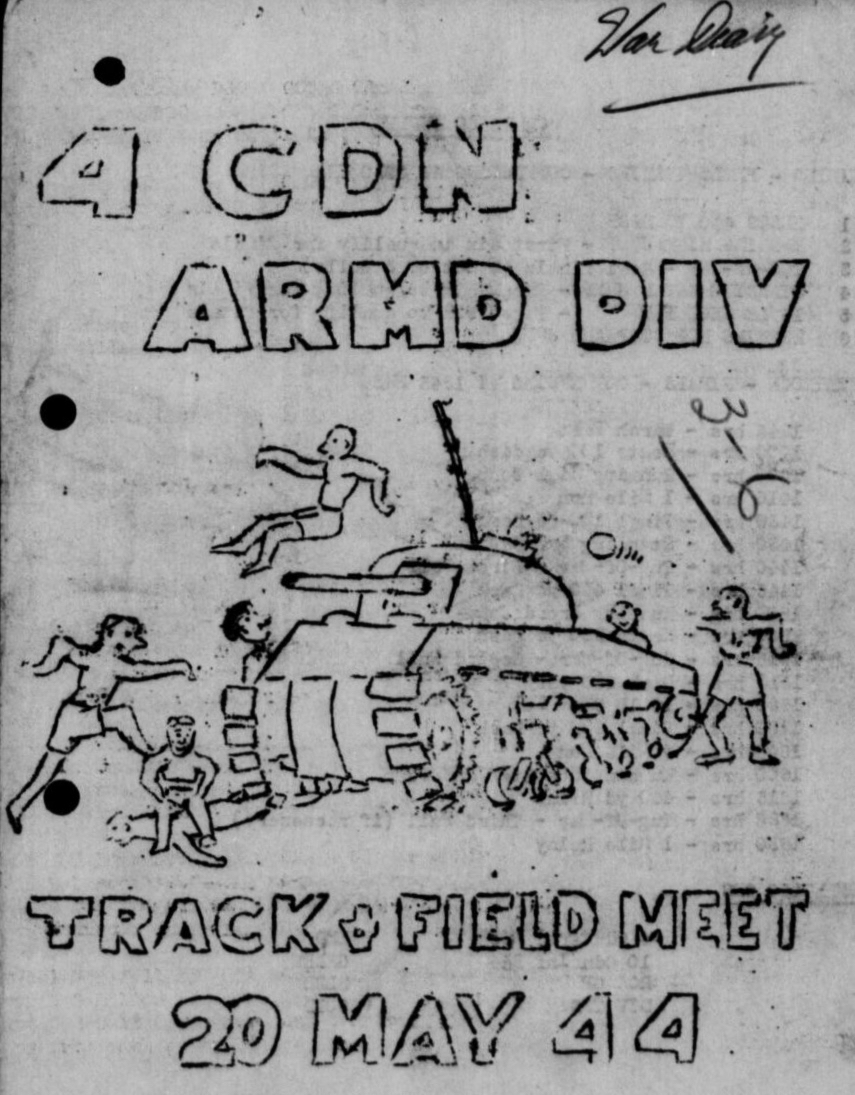

The daily accounts of the regiment for the first couple of years of the war were brief and basic, often consisting of weather reports and training notes. I skimmed along hoping for nuggets of information that would help me build a story of Vincent’s life in the army. In addition to the journal entries, the scanners had included rosters, posters and even cartoons that had been tucked between the pages. Eventually I spotted Vincent’s name on a set of Battalion Orders dated 12 July 1941, which showed that he had been assigned to ‘B’ Company — not surprisingly, the regimental band. I found his name several more times in the postings over the years through the training period.

The units often held track and fields competitions, and posters for these events were inserted into the war diaries (source: Canadian War Diaries)

The insertions proved to be fascinating, and I perused them even more closely than the daily logs. Even the documents that didn’t list names offered insight into life at the training camps.

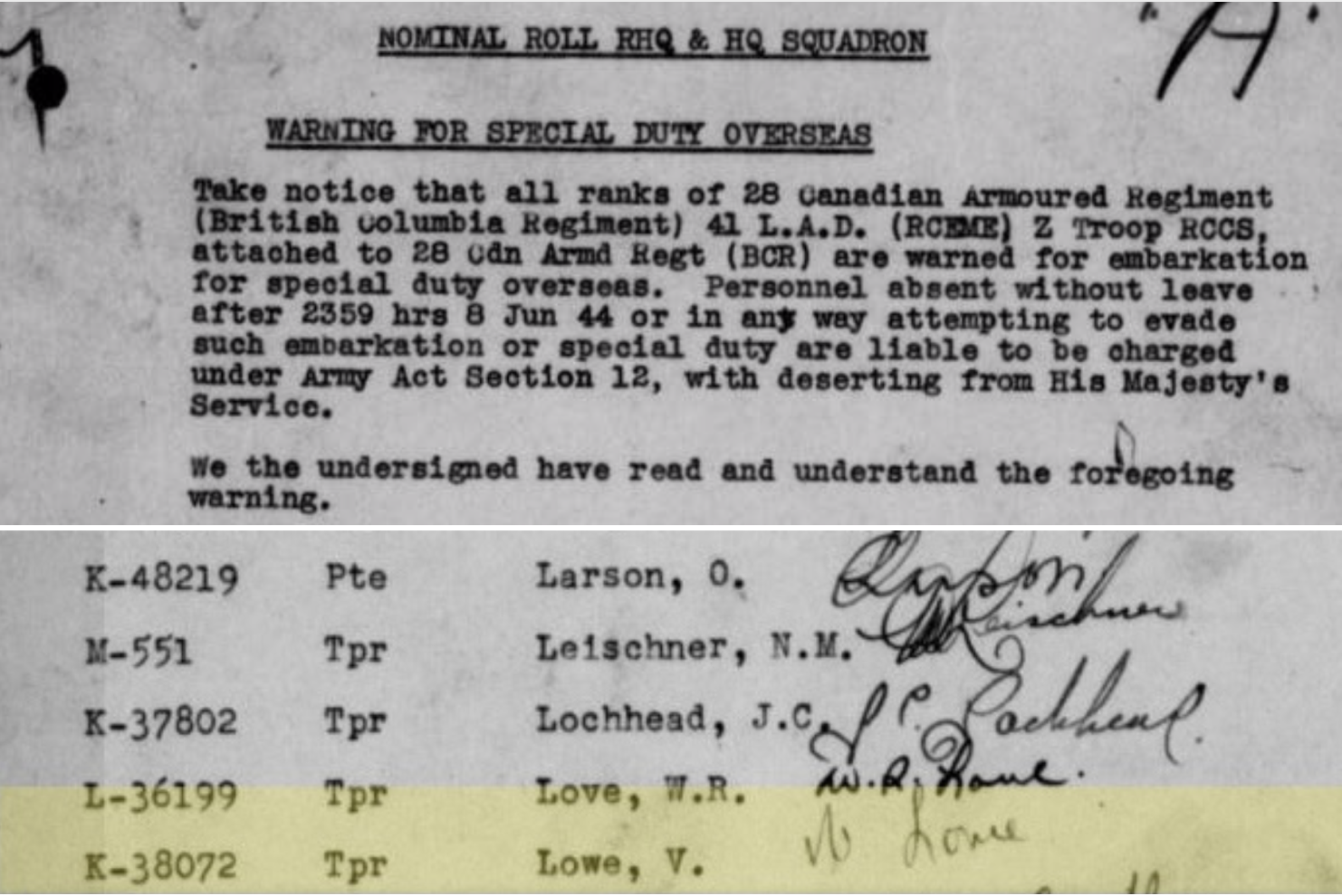

As D-Day grew closer, the seriousness of the situation became clear when I found my uncle’s name again, but this time in a more ominous roster than his posting to the regimental band. The multi-page “Warning for Special Duty Overseas” required that all soldiers sign to indicate their understanding of the orders.

My uncle’s name and signature in the Nominal Roll for Special Duty Overseas from 1944 (source: Canadian War Diaries)

Undated but in with the records for the spring of 1944, this roster was obviously done in preparation for D-Day, but how long before is not evident. The date soldiers were required to return to camp was 8 June 1944, two days after what would become D-Day. This made me wonder if D-Day had been initially planned for a later date or if Vincent’s regiment was never expected to be in the first wave.

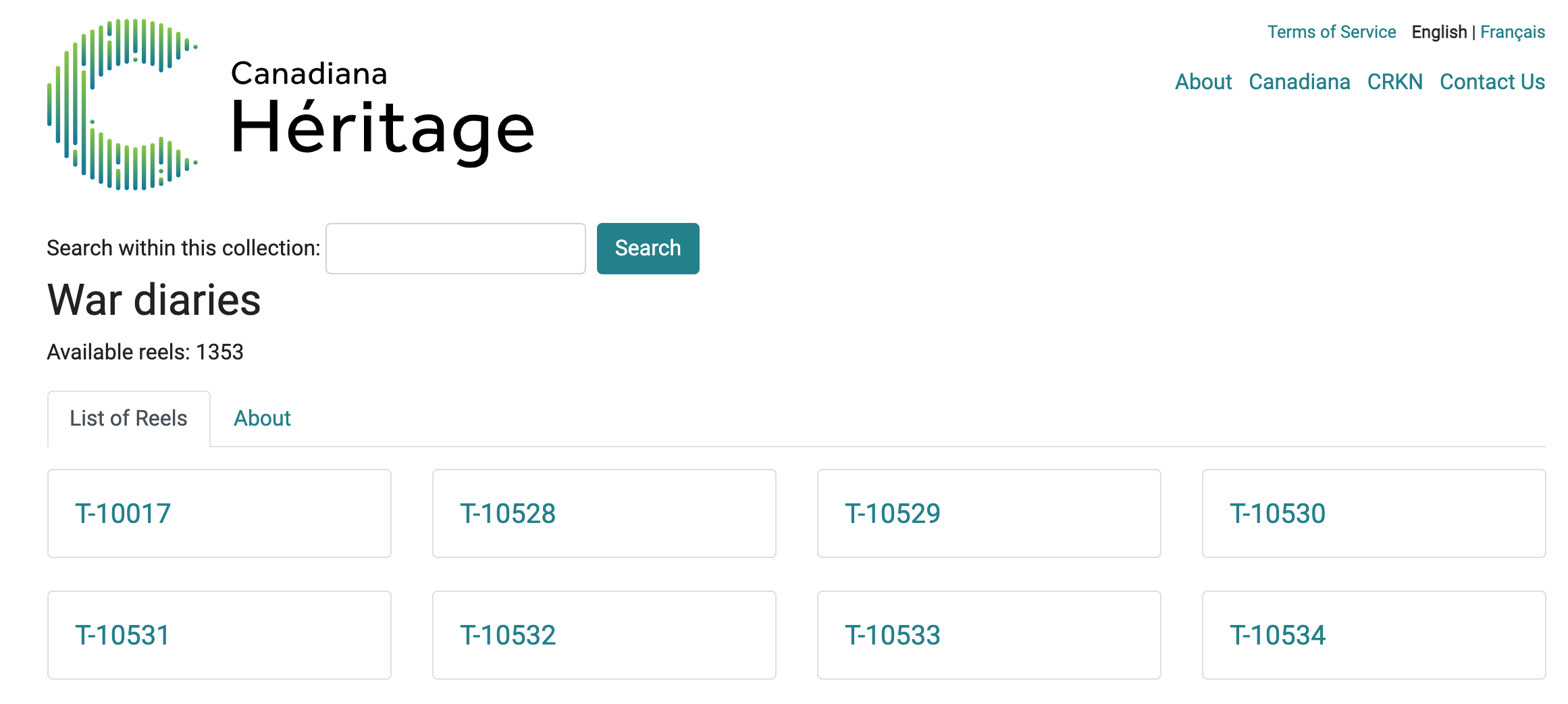

On 4 April 1944, a message was received by the regiment from the Commander-in-Chief of the 21st Army Group: General Montgomery. The message header stated that it was to be read to all troops, which told me that my Uncle Vincent would have heard this message in person. The letter began, “The time has come to deal the enemy a terrific blow in Western Europe. The blow will be struck by the combined sea, land, and air forces of the Allies…” The was a chilling reminder of just what my uncle and his regiment were training for. A similar letter from Eisenhower followed.

…a chilling reminder of just what my uncle and his regiment were training for.

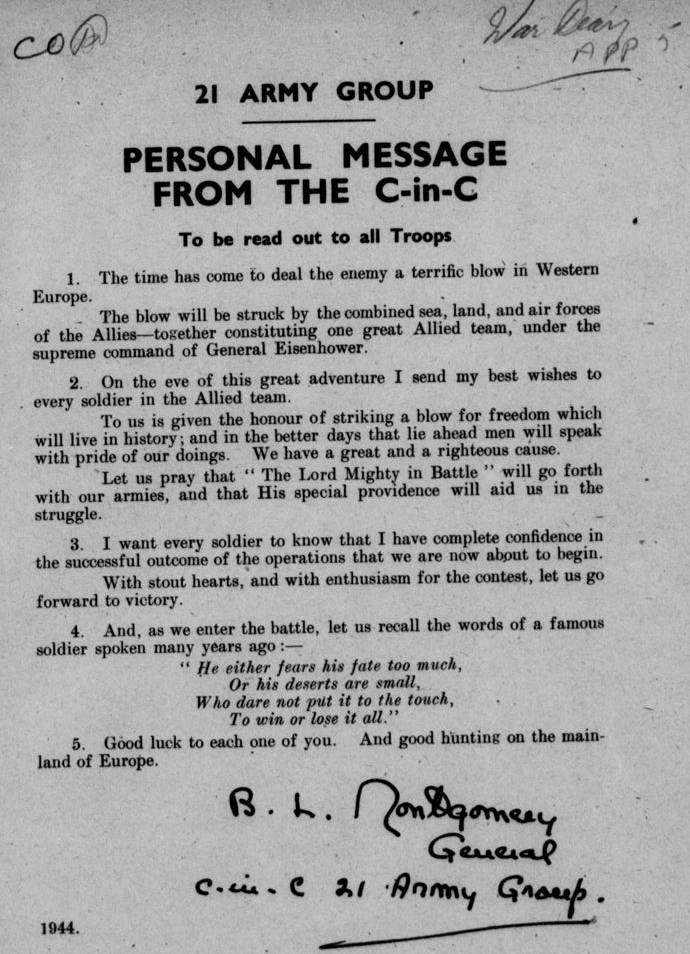

When the date for D-Day was finally set, the message read simply, “Confidential. D Day 6 Jun 44.” The ominous memo was slipped in between the pages of the war diaries along with the mundane bureaucratic documentation.

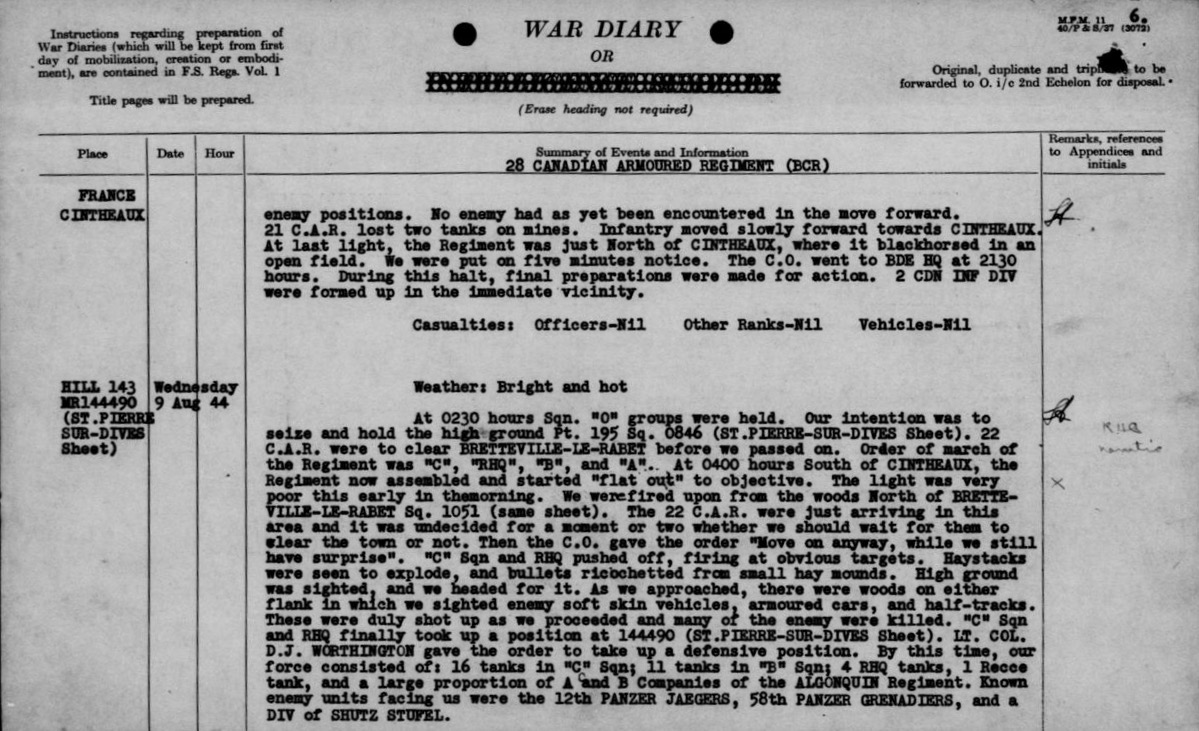

Vincent’s regiment was not in the first wave and arrived in Europe 24 July 1944. The war diaries followed them through France into Belgium, on to Holland and finally into Germany. Field returns, casualty lists, and topographic maps documented the regiment battle-by-battle until the end of war in Europe.

Intelligence Summary for June 6-9, 1944 at Warren Camp, Sussex, England (source: Canadian War Diaries)

As I read through the daily entries for my uncle’s regiment, many of them tragic, I gradually acquired an understanding of what it might have been like for Vincent and the other soldiers.

Account of BC Regiment’s encounter with the enemy 9 August 1944 in France (source: Canadian War Diaries)

Since discovering the war diaries, I’ve watched film documentaries about the battles I now know Vincent’s regiment fought in, and I have been able to add a visual element to my uncle’s experience. I’d seen many documentaries of the war during my life, but personally knowing someone who was there changed how I viewed the film footage. Suddenly, the horrific images were personal, and they helped me understand why Vincent chose not to discuss his war experience.

The combination of service records, war diaries and documentaries are building an account of my uncle’s military service that was previously unavailable in our family. (K. M. Lowe)

Find the World War II War Diary scans at Heritage Canadiana

Find the index at WARTIMES.ca